Kicked Out

Newsletter 2022-04-11

I made a horrible, stupid, unforgiveable mistake. My kids wanted to play soccer, and I said, “Yes.” I almost always do. My role in this family is to cause as much chaos as possible, a job I usually fulfill eagerly and with much relish. But this time, it backfired. When I signed up my youngest three daughters for soccer months ago, I figured it would just be one more commitment a week. How bad could it be? Pretty bad, it turns out. Now that soccer season is finally here, I realize that I failed to take into account basic math. Once again, numbers have conspired to ruin my life.

I wasn’t thrilled when my youngest three asked to join Cub Scouts, but it was only one hour a week. I could act like a fun dad in triplicate by taking them all to the same place during the same time slot, no extra trips required. Parenting is all about economies of scale. I thought the same thing would happen in soccer. Not a chance. I discovered last week that all three kids are in different age brackets. No, I wasn’t surprised by their ages (although I do constantly get them wrong because they have the audacity to have birthdays every single year), but I didn’t really think about how they would be distributed in a team system. In my mind, they’re all one unit, forever doomed to be picked up and dropped off together. Youth soccer saw things differently. The season only lasts for six weeks, with one game and one practice per week. Even someone as lazy as me could handle that. But since the kids are split up into three different age brackets, I collectively have to take them to eighteen games and eighteen practices over a month and a half. Plus there’s an extra optional practice for each kid each week to develop basic soccer skills (Don’t use your hands; kick the ball, not each other; no eye gouging.) In sports, “optional” always, always means mandatory because all athletic lingo was developed by the Ministry of Truth. The technical practices are for multiple teams at once, so two of the three kids could double up, but it was still an extra twelve practices total. Then we found out that our nine year old, Mae, has additional games on days other than Saturday, and instead of being local, many of them are away at fields forty-five minutes from our house. There’s one weekend where she has games Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, two of which might as well be on the other side of the world. It’s not like she’s on some elite traveling team, either. This is literally the first time she’s ever played soccer, but nine is apparently the age where sports transition from fun extracurriculars to serious business. I’m guessing there will be professional scouts at all of her games to find the next David Beckham, which seems a bit pointless since professional soccer doesn’t actually exist. Don’t argue. No one in America has ever actually seen a game played by the MLS. The end result is, instead of twelve extra commitments total over six weeks, we ended up with more than fifty. My life is officially out of control.

For years, I’ve heard tales of parents who become glorified taxi services for their kids, but I’d avoided that fate up until now. Life was better when my kids were only vaguely aware of the outside world. You can’t sign up for things if you never leave the house. Here was my driving schedule Thursday night, when two kids had soccer practices that overlapped with Cub Scouts: home to soccer to drop off my six-year-old, Waffle; soccer to home to pick up my seven-year-old, Lucy; home to soccer to drop off Lucy; soccer to home to pick up Mae; home to Cub Scouts to drop off Mae; Cub Scouts to soccer to pick up Lucy; soccer to Cub Scouts to drop off Lucy; Cub Scouts to soccer to pick up Waffle; soccer to Cub Scouts to drop off Waffle, but that time I stayed at Cub Scouts so Waffle could endanger my fingers while building a birdhouse. I typed this entire newsletter with my elbows. I handled all of those trips, but there are other nights where the unpaid Uber duties will fall entirely on my wife Lola. It took a NASA supercomputer to line up our schedules and figure out who would drive who where and when. On any given day, there’s only a fifty-fifty chance we’ll show up at the right place with the right kid. I’m hoping that my daughters don’t notice and also that their coaches can’t tell them apart.

The villain here is the youth sports system in general, not the people who staff it. The coaches and referees are just parents who got roped into helping out instead of army crawling out of the room like me when the organizers asked for volunteers. As far as I’m concerned, every single coach is a leading candidate for sainthood. They’re trying to create better athletes and better people, but they’re also at constant risk of being trampled to death by an unruly pack of kindergartners. Those cleats hurt. Altruism, while admirable, is a hair’s breadth away from being a mental illness. I expect to see every coach’s name on the in memoriam list at the end of the season.

As much as I complain about the unexpected technical practices that take up extra time slots each week, my kids are probably the ones who need them the most. It’s not that they’re uncoordinated, although my genes didn’t do them any favors in that department. They mainly need the extra practices because I’ve kept them sheltered from sports until now. When they look back on their childhoods, I hope they remember fondly the early years of all screen time and no sunlight. Serious athletes signed up for their first soccer leagues moments after they barrel-rolled out of the womb. At nine, Mae is basically a grandmother in the sport, despite never having played a game. When my oldest daughter, Betsy, started middle school in the fall, she didn’t even consider signing up for soccer because the other kids at tryouts had already been playing for a decade, which is impressive since they were all only eleven years old. Mae isn’t quite to that point, but the clock is ticking. She’s got a month to either become the next Pelé or give up on ball sports forever. That doesn’t have to be the end of her athletic career, but it does mean her sports options will be limited to running, which is a fate worse than death. I should know. I ran cross country and track from junior high through college, and every time I take a step, it sounds like my knees are crumpling up a candy wrapper.

All the downsides I’ve talked about so far mostly apply to the only person who matters in all my stories: me. The kids, on the other hand, are super excited to play soccer. Mae, in particular, seems to love the sport, despite her combined lifetime experience with it being two practices and one game. She’s naturally athletic, which is something I can’t relate to at all. She’s also popular and outgoing, which likely means she was swapped with my actual child at birth. She likes soccer because she gets to hang out with her friends and kick stuff, which, I must admit, sounds like a solid day. She’s convinced that she’ll be great at it, and maybe she will be. The first step to accomplishing anything is believing in yourself—or at least not doubting yourself to the point where you give up before you even get started. There’s a transition that happens in kids as they get older, and it’s heartbreaking. Small children start out with unjustified self-confidence. Before Mae, Lucy, or Waffle tries something for the first time, they honestly believe they could be the best in the world at it eventually—or right now. They don’t necessarily expect to set the all-time high score at the whack-a-mole game at Chuck E. Cheese, but they ask you what the world record is just in case. (If you were curious, it was set by Mr. Cheese himself, which seems suspicious. That record should come with an asterisk.)

Somewhere along the line, though, kids start to assume the outcome of any new situation will be failure instead of success. Rather than thinking that they’ll be the greatest ever, they worry that they’ll be such a colossal screw up that everyone will laugh at them. This condition is endemic among middle schoolers. The first time a sixth grader tries something new, the only result they can imagine is that they’ll embarrass themselves in front of everyone. It’s a shame because, if there’s one time in their lives when they can go for broke with virtually no consequences it’s junior high. I fell into the same trap at that age. I was convinced I couldn’t try new things for fear of looking stupid in front of my classmates. Yet twenty-five years later, not a single one of those people even remembers that I exist. Heck, I barely even remember me from back then. If I were to string together every memory I have from sixth grade in a single video, it would be less than three minutes long, and two of those would just be commercials that will forever be stuck in my head. If my brain was half as good at remembering numbers as it is at pointlessly clinging to useless bits of pop culture, I could have majored in a STEM field instead of English. Maybe then I could have correctly calculated how many soccer practices my kids would actually have.

The transition from, “Yes, I can,” to, “No, I can’t,” isn’t entirely self-imposed. Reality has a bad habit of pushing back. It’s fun to tell little kids they can be anything they want to be when they grow up, but the truth is they can’t grow up to be a firetruck, no matter how hard they study in firetruck school. I don’t know how many hopeful children ever thought they could one day be U.S. president, but it was significantly more than the forty-six who actually did. My own self doubt is justified by years of empirical data. The evidence is pretty much anything I’ve ever done. You haven’t truly failed at changing a tire until you snap a tire iron in half. That thing is solid metal. We’re talking super villain henchman levels of incompetence here. But there has to be a middle ground. My kids probably won’t be the greatest soccer players ever to live, but there’s no way they’ll be the worst. And in the extremely unlikely event that they are literally the worst child athletes in the history of mankind, would it even matter? There’s no law that says you can’t have fun at something you’re bad at. I love playing Halo, yet I spend every Friday night of my life getting destroyed by thirteen year olds who weren’t even born when I started playing the game. Even Waffle beats me sometimes, even though I’ll never admit it to her. I’m dreading the day when she’s finally old enough to read her own score. It’s a cliché that it’s not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game. Some people think that’s loser talk because, well, it is. But I don’t care how my kids play the game, either. There’s a ninety percent chance one or more of them will spend every soccer game just picking grass. It’s not whether you win or lose, but whether you enjoy yourself while you’re doing it. If they have fun destroying the ground cover, then more power to them. And if they don’t like tearing up grass or playing soccer, they could always sign up for something else. Or simply stay home. My gas budget would be grateful.

***

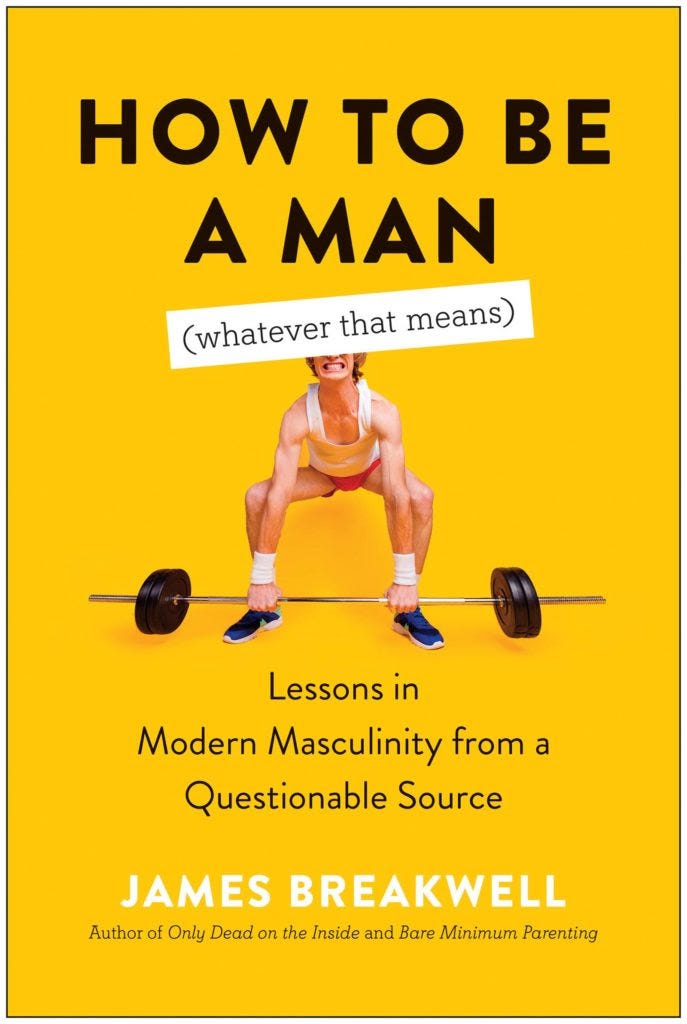

I confused my kids the other day. I referenced the lawn gnome story, the most traumatic/hilarious incident from all my years in college, and they had no idea what I was talking about. Of course they didn’t know. I wrote it out in How To Be A Man (Whatever That Means): Lessons In Modern Masculinity From a Questionable Source and gave each of my children a free copy, which guarantees they’ll never read it. I can’t blame them. They’re a little young, and also it’s super uncool to read about your own dad. That hasn’t stopped thousands of other people from enjoying the completely true stories in this book. It’s the most personal thing I’ve ever written, and, in the opinion of many readers, the funniest. It’s also the only book that made my editor cry, and not from typos. (At least I hope not.) For a more unbiased assessment, here’s a reader review:

Kindle Customer

5.0 out of 5 stars

Humor in life, love, and the pursuit of happiness

James Breakwell never disappoints - his family friendly humor remains in tact in his latest book How to Be a Man (Whatever That Means). Honestly it could be called how to be a human being, because while he plays up all the best tropes and stereotypes and pokes fun at the male gender, one positive lesson you walk away with is that as humans we're all just trying our best, or just trying, or appear to be trying, or just exist... But let's face it, by making this book gender-specific Breakwell appeals to our darker side, where we want him to spill all the tea on the men in our lives. Tea is best served with a side of sarcasm.

Sharing real-life anecdotes of his past (or made up anecdotes, because honestly how would we know?), James Breakwell's sly humor will make you smile and sometimes laugh out loud, and once in a while tear up in a very sentimental way as he covers family, finances, parenting, surviving university, and a variety of other topics. He also occasionally allows himself to be vulnerable, and that is such a priceless gift. But most of the time he stays on the humorous side of real-life situations that are wacky enough to be true. One way that this book differentiates itself from his past works is that we get more of Breakwell the man than we do James Breakwell the father. Many of the stories here predate him becoming a dad - we get tales of his childhood, teenage angst, and college years and how those experiences formed the man he is today.

How to Be a Man is great for long-time readers of the author as well, as we learn some of the juicy details behind stories we're familiar with, such as his ownership of two mini-pigs, his purchase of a [maybe haunted?] fixer-upper home, and how he proposed to his wife Lola. Reading a James Breakwell book is like talking to an old friend who tells funny stories to pass the time, one you may know really well (depending on how many facts have been changed to protect the innocent and the not-so-innocent from his growing fame) and that you're always glad you've run in to.

You can get the book here: The best stories.

Anyway, that’s all I’ve got for now. Catch you next week.

James

Copyright © 2022 James Breakwell, All rights reserved.

Our mailing address is:

7163 Whitestown Pkwy #268

Zionsville, IN 46077